If you have questions or want to learn more, please fill in the form or send us an email at:

Parking Reform is Working in Minneapolis

This spring, a 23-unit apartment, called Solstice, will begin to lease in a centrally located but fairly low-density neighborhood of Minneapolis. As a certified passive house development, Solstice will have a substantially lower carbon footprint than most new apartments. But that’s not the only remarkable thing about this project: Solstice will also have a grand total of zero parking spots.

The Solstice project is only possible because Minneapolis eliminated all minimum parking mandates in May 2021, soon after passing its 2040 Comprehensive Plan. The total elimination of parking mandates followed a 2015 change that greatly reduced parking mandates near high-frequency transit. Before implementing these policies, most housing in Minneapolis had typically required one parking space per unit.

Minimum parking mandates are pervasive in the land use rules of American cities. Take, for example, a rule from neighboring Saint Paul before they also eliminated minimum parking mandates: golf courses would need four parking spaces per hole, but mini golf courses would need just one space per hole.

When applied to housing, this kind of rigidity becomes extremely consequential. Minimum parking mandates cannot precisely estimate the demand for parking at every new development, which will vary immensely across different contexts. Inevitably, there will be housing developments for which these mandates require parking in excess of demand.

That excess parking comes at a very high cost. Parking is expensive; building structured parking can cost tens of thousands of dollars per spot. And it takes up space, too — space that could go toward building additional units of housing. The additional cost and limited flexibility of parking mandates can render some much-needed housing projects financially infeasible.

Measuring the Effect of Parking Reform

The best way to assess whether parking mandates result in excess parking is to see what happens in their absence. Since 2021, developers in Minneapolis have started to build new housing with significantly less parking, suggesting an untapped demand for parking-free or parking-light housing options.

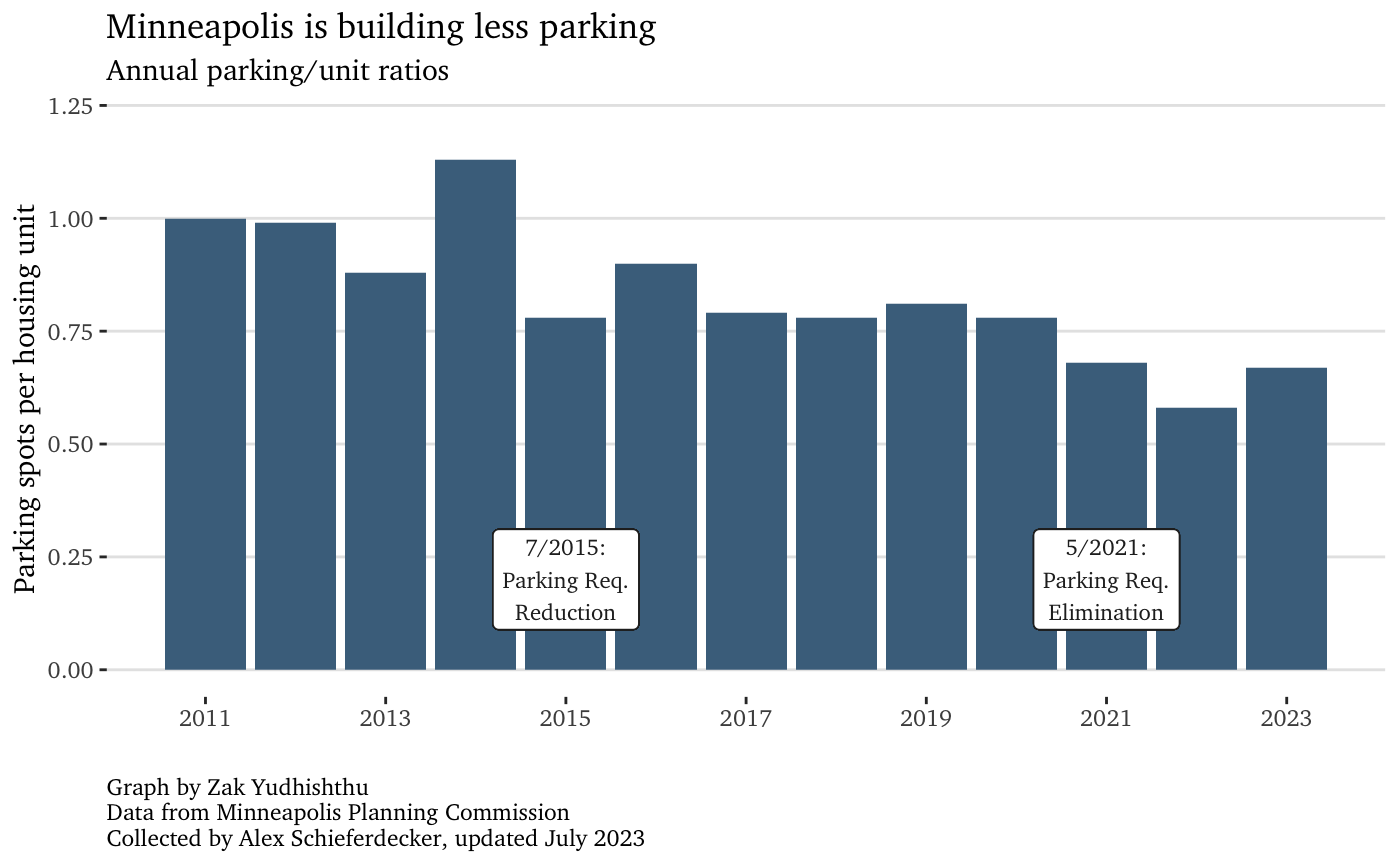

As my graph below shows (originally published in the Minnesota Reformer), among new multifamily homes in Minneapolis, the average number of parking spots per new unit of housing has fallen from about 1 spot per unit to under 0.75 spots per unit. The graph uses data on approved multifamily housing developments from the Minneapolis Planning Commission, which tracks counts of housing units and parking spots.

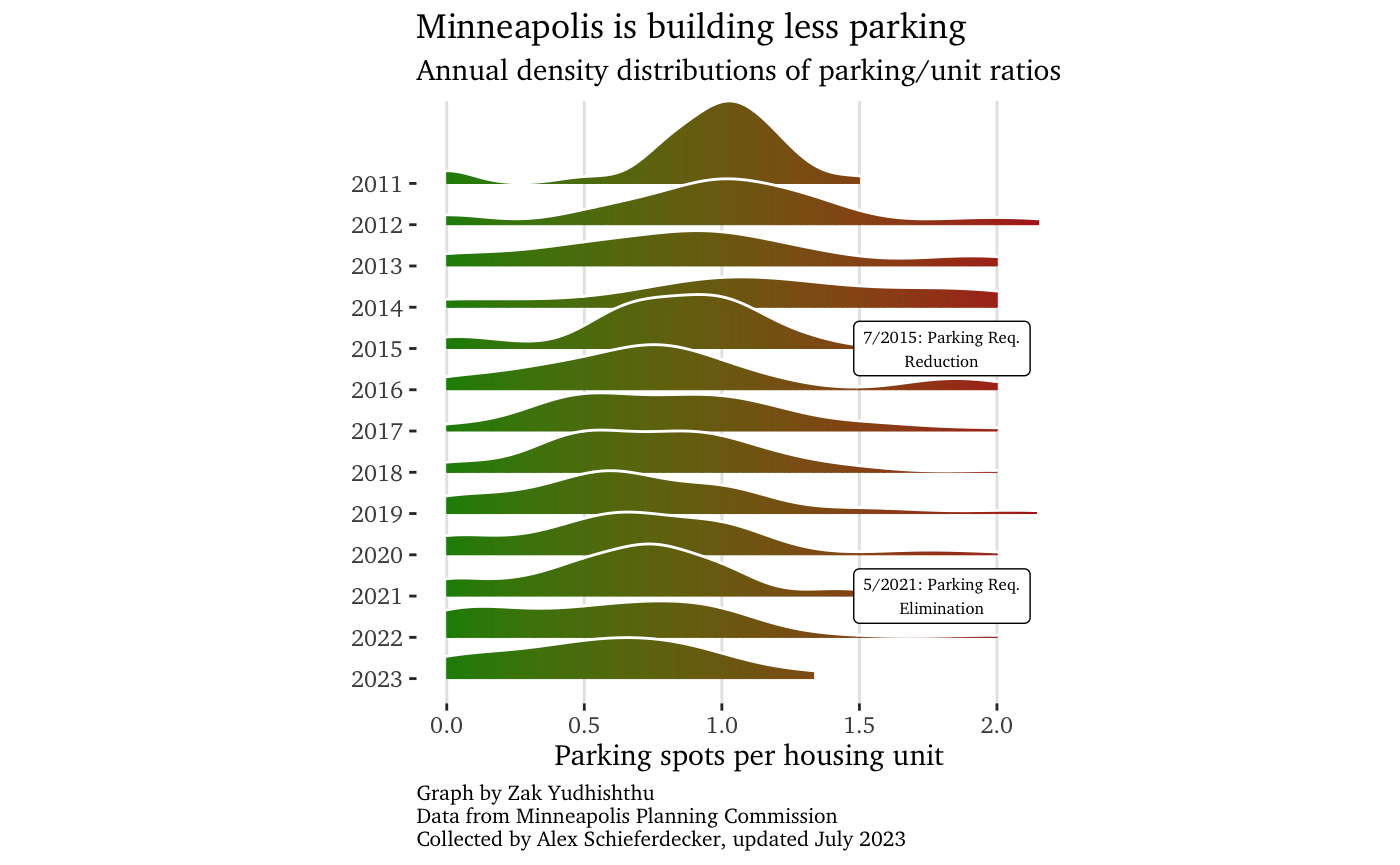

Averages don’t tell the whole story. Equally important is any decline in the distribution of per-unit parking across new buildings. It wasn’t just the average parking-to-unit ratio that fell; a growing share of new buildings have very little parking, or none at all.

The chart below shows the shifting distribution of parking-unit ratios in new Minneapolis developments by year. While a few developers have continued building about one parking spot per housing unit, the large majority of new housing comes with less parking than this.

Minneapolis has added a lot of housing over the past few years, helping to keep rental growth in check relative to many peer cities. Eliminating parking requirements was a key component of Minneapolis’s winning formula, which also included legalizing higher levels of density in various parts of the city and reducing the need for variances when permitting new development.

Such reforms are complementary. Legalizing more kinds of housing to increase density will contribute to more housing abundance, but it will be even more effective if newly legalized housing typologies don’t require a bunch of new parking spots.

Getting rid of minimum parking mandates also makes it easier to accommodate change over time. Although not every neighborhood is ready for parking-light housing today, more will be in the future. And as we work to build cities with better transit and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, the demand for parking in new developments will decline.

This will contribute to a virtuous cycle where lower demand for parking leads to the construction of more low- or no-parking developments, which in turn add more residents who don’t own their cars — and, in the process, create more local demand for transit and active transportation infrastructure. Freedom from the parking mandate is a crucial mechanism for both supporting and adapting to more abundant, sustainable cities.

Zak Yudhishthu writes about and researches housing policy in the Twin Cities, and works for the organization Sustain Saint Paul.