If you have questions or want to learn more, please fill in the form or send us an email at:

What’s Up with Austin’s Falling Rents?

Like many other southern metros, the Austin area experienced a surge of newcomers during the pandemic, adding 173,000 people between 2020 and 2023. That’s a 7.5% growth rate at a time when the total United States population only grew by 1%. This increased demand drove up housing prices across the region, with average rents jumping 28% between March 2020 and July 2022.

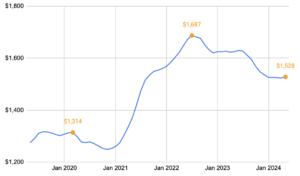

Since then, average rents have fallen by more than 9%, as shown in Figure 1—a disaster according to the real estate press and Austin’s haters, but good news for the 55% of Austinites who do not own a home.

How did Austin make this happen? In short, cities across the Austin metropolitan area built a lot of housing.

Figure 1: Average Effective Rents in Austin (May 2019 – May 2024)

While “Austin” has received much praise for achieving this feat, it’s important to distinguish between the city and the metro area. The Austin Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) includes five counties: Williamson, Hays, Caldwell, Bastrop, and Travis, where Austin mainly sits. The latest Census data shows that the vast majority of population growth in what we call “Austin” was actually in its surrounding suburbs. Indeed, while the MSA population excluding Austin surged by 12% between 2020 and 2023, as seen in Figure 2 below, the city itself grew by less than 1.5%, creating an observable “donut effect.”

Figure 2: Change in Austin MSA Population by County

So, it was Austin’s suburbs that largely absorbed the influx of newcomers—because that was where the housing was. Compare the number of multifamily housing units permitted in the Austin and San Francisco MSAs. As seen below in Figure 3, Austin permitted a huge number of multifamily units in the years after the Great Recession, reaching a high of 26,421 units in 2021 compared to San Francisco’s most recent high of 13,373 units in 2018.

Figure 3: Multifamily Housing Units Permitted in Austin MSA vs San Francisco MSA

According to Apartment List, Austin permitted 9.2 new multifamily units per every 1,000 residents, a rate that was 61% higher than the next highest metro, Raleigh—or 3.5 times the rate in New York and 9.2 times the rate in San Francisco. Austin has led the nation in multifamily permitting for seven years, and even with a slowdown this year, it is still on pace to top the list.

This sustained multi-year increase in the number of multifamily apartments eventually outpaced demand as the pandemic population surge slowed down. Even so, average rents remain elevated above pre-pandemic levels across the metro area.

Austin’s suburbs were able to absorb so many newcomers because it was relatively easy to build housing in those jurisdictions—and it is to those fast-growing jurisdictions that much of the credit is due, as shown in Figure 4 below. While Austin’s suburbs have long supported the construction of new housing, the city itself has only recently begun saying “yes in my backyard.”

Figure 4: Change in Population of Austin MSA’s Fastest Growing Cities

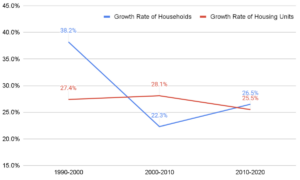

The City of Austin is an easier place to build than New York and San Francisco, but it has the highest development fees among big cities in Texas and one of the most cumbersome permitting systems. Still, from 2010 to 2020, the city managed to build 90,000 housing units, according to the City’s Planning Department. In any other context, this would have been amazing news. But over the same period, Austin’s booming economy and robust job creation attracted significant newcomers, and the population grew by 22%, or 175,000 people. Unfortunately, the growth of households outpaced the growth in housing units, creating a supply-demand imbalance, seen in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Growth in Austin Households Outpaces Growth in Housing Units

The pandemic further exacerbated that dynamic, as remote work led to the formation of new households and an influx of telecommuters. Home prices and apartment rents skyrocketed, causing affordability to become a big issue in the 2022 City Council elections. That year, Austin elected a slate of pro-housing candidates to City Council. All of a sudden, nine out of eleven council members supported more housing — a political sea change.

In the years before the 2022 elections, City Council had enacted several piecemeal measures that upzoned and eliminated parking mandates downtown, leading to a transformation of Austin’s skyline. The council also created several housing affordability programs, including the highly successful Affordability Unlocked program, which expedited the permitting process and loosened restrictions on height, density, and parking. As a result, the program fueled the creation of some 6,100 income-restricted homes.

But before 2022, Austin had not undertaken a major rewrite of its land development code since 1984. The last attempt to do so, the ill-fated CodeNEXT process, began in 2012, cost $10 million, and was eventually voided in court in 2020. (The attempted rewrite met its final end in 2022 when an appeal of the 2020 court decision failed.)

Which brings us back to the present day. Since the 2022 election, the City Council supermajority has undertaken an ambitious set of citywide reforms, including:

- Allowing three housing units by right on any single-family lot

- Reducing the minimum lot size for a single home from 5,750 to 1,800 sq. ft.

- Rolling back “compatibility” height restrictions that were suppressing more than 70,000 housing units

- Creating a new density bonus program that allows for the redevelopment of commercial spaces into more housing

- Eliminating parking mandates citywide

If Austin passes a pending single-stair reform proposal, it will solidify the city’s reputation as one of the YIMBY capitals of America. Yet, while these major policy victories should rightly be celebrated, they did not cause the recent decline in rents. And falling rents are not a sign that we have built too much housing: the low rents are attracting renters, and as a result Austin had the second-highest apartment demand in the past quarter, per RealPage.

But by undertaking these far-reaching and long-term reforms, the City of Austin is setting itself up for a more abundant future in which people who want an urban lifestyle won’t have to decamp for the suburbs—though there’s plenty of room out there for folks who want that, too. We like to say that in Austin, “y’all means all.” In the city, our housing policy is finally starting to reflect that ideal.